Lorentz force

| Electromagnetism | ||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

Electricity · Magnetism

|

||||||||||||

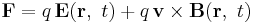

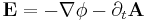

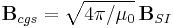

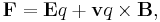

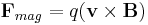

In physics, the Lorentz force is the force on a point charge due to electromagnetic fields. It is given by the following equation in terms of the electric and magnetic fields:[1]

where

- F is the force (in newtons)

- E is the electric field (in volts per metre)

- B is the magnetic field (in teslas)

- q is the electric charge of the particle (in coulombs)

- v is the instantaneous velocity of the particle (in metres per second)

- × is the vector cross product

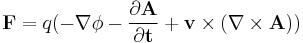

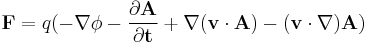

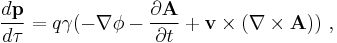

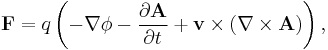

or equivalently the following equation in terms of the vector potential and scalar potential:

where:

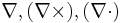

- ∇ and ∇ × are gradient and curl, respectively

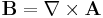

- A and ɸ are the magnetic vector potential and electrostatic potential, respectively, which are related to E and B by[2]

Note that these are vector equations: All the quantities written in boldface are vectors (in particular, F, E, v, B, A).

The Lorentz force law has a close relationship with Faraday's law of induction.

A positively charged particle will be accelerated in the same linear orientation as the E field, but will curve perpendicularly to both the instantaneous velocity vector v and the B field according to the right-hand rule (in detail, if the thumb of the right hand points along v and the index finger along B, then the middle finger points along F).

The term qE is called the electric force, while the term qv × B is called the magnetic force.[3] According to some definitions, the term "Lorentz force" refers specifically to the formula for the magnetic force:[4]

with the total electromagnetic force (including the electric force) given some other (nonstandard) name. This article will not follow this nomenclature: In what follows, the term "Lorentz force" will refer only to the expression for the total force.

The magnetic force component of the Lorentz force manifests itself as the force that acts on a current-carrying wire in a magnetic field. In that context, it is also called the Laplace force.

History

Early attempts to quantitatively describe the electromagnetic force were made in the mid-18th century. It was proposed that the force on magnetic poles, by Johann Tobias Mayer and others in 1760, and electrically charged objects, by Henry Cavendish in 1762, obeyed an inverse-square law. However, in both cases the experimental proof was neither complete nor conclusive. It was not until 1784 when Charles-Augustin de Coulomb, using a torsion balance, was able to definitively show through experiment that this was true.[5] Soon after the discovery in 1820 by H. C. Ørsted that a magnetic needle is acted on by a voltaic current, André-Marie Ampère that same year was able to devise through experimentation the formula for the angular dependence of the force between two current elements.[6][7] In all these description, the force was always given in terms of the properties of the objects involved and the distances between them rather than in terms of electric and magnetic fields.[8]

The modern concept of electric and magnetic fields first arose in the theories of Michael Faraday, later to be given full mathematical description by the likes of William Thomson and James Clerk Maxwell. J. J. Thomson was the first to apply the concept of fields to determine the electromagnetic forces on an object in terms of the object's properties and external fields. Interested in determining the electromagnetic behavior of the charged particles in cathode rays, Thomson published a paper in 1881 wherein he gave the force on the particles due to an external magnetic field as  . Thomson was able to arrive at the correct basic form of the formula, but, because of some miscalculations and an incomplete description of the displacement current, included an incorrect numerical coefficient in front of the formula. It was Oliver Heaviside, who had invented the modern vector notation and applied them to Maxwell's field equations, that was able to correctly derive in 1885 and 1889 the correct form of the magnetic force on a charged particle.[9] Finally, in 1892, Hendrik Lorentz derived the modern day form of the formula for the electromagnetic force. Lorentz began by abandoning the Maxwellian descriptions of the ether and conduction. Instead, Lorentz made a distinction between matter and the luminiferous aether and sought to apply the Maxwell equations at a microscopic scale. Using the Heaviside's version of the Maxwell equations for a stationary ether and applying Lagrangian mechanics, Lorentz arrived at the correct and complete form of the force law that now bears his name.[10]

. Thomson was able to arrive at the correct basic form of the formula, but, because of some miscalculations and an incomplete description of the displacement current, included an incorrect numerical coefficient in front of the formula. It was Oliver Heaviside, who had invented the modern vector notation and applied them to Maxwell's field equations, that was able to correctly derive in 1885 and 1889 the correct form of the magnetic force on a charged particle.[9] Finally, in 1892, Hendrik Lorentz derived the modern day form of the formula for the electromagnetic force. Lorentz began by abandoning the Maxwellian descriptions of the ether and conduction. Instead, Lorentz made a distinction between matter and the luminiferous aether and sought to apply the Maxwell equations at a microscopic scale. Using the Heaviside's version of the Maxwell equations for a stationary ether and applying Lagrangian mechanics, Lorentz arrived at the correct and complete form of the force law that now bears his name.[10]

Trajectories of particles in a Lorentz force

In many cases of practical interest, the motion in a magnetic field of an electrically charged particle (such as an electron or ion in a plasma) can be treated as the superposition of a relatively fast circular motion around a point called the guiding center and a relatively slow drift of this point. The drift speeds may differ for various species depending on their charge states, masses, or temperatures, possibly resulting in electric currents or chemical separation.

Significance of the Lorentz force

While the modern Maxwell's equations describe how electrically charged particles and objects give rise to electric and magnetic fields, the Lorentz force law completes that picture by describing the force acting on a moving point charge q in the presence of electromagnetic fields.[1][11] The Lorentz force law describes the effect of E and B upon a point charge, but such electromagnetic forces are not the entire picture. Charged particles are possibly coupled to other forces, notably gravity and nuclear forces. Thus, Maxwell's equations do not stand separate from other physical laws, but are coupled to them via the charge and current densities. The response of a point charge to the Lorentz law is one aspect; the generation of E and B by currents and charges is another.

In real materials the Lorentz force is inadequate to describe the behavior of charged particles, both in principle and as a matter of computation. The charged particles in a material medium both respond to the E and B fields and generate these fields. Complex transport equations must be solved to determine the time and spatial response of charges, for example, the Boltzmann equation or the Fokker–Planck equation or the Navier-Stokes equations. For example, see magnetohydrodynamics, fluid dynamics, electrohydrodynamics, superconductivity, stellar evolution. An entire physical apparatus for dealing with these matters has developed. See for example, Green–Kubo relations and Green's function (many-body theory).

Although one might suggest that these theories are only approximations intended to deal with large ensembles of "point particles", perhaps a deeper perspective is that the charge-bearing particles may respond to forces like gravity, or nuclear forces, or boundary conditions (see for example: boundary layer, boundary condition, Casimir effect, cross section (physics)) that are not electromagnetic interactions, or are approximated in a deus ex machina fashion for tractability.[12]

Lorentz force law as the definition of E and B

In many textbook treatments of classical electromagnetism, the Lorentz Force Law is used as the definition of the electric and magnetic fields E and B.[13] To be specific, the Lorentz Force is understood to be the following empirical statement:

- The electromagnetic force on a test charge at a given point and time is a certain function of its charge and velocity, which can be parameterized by exactly two vectors E and B, in the functional form:

If this empirical statement is valid (and, of course, countless experiments have shown that it is), then two vector fields E and B are thereby defined throughout space and time, and these are called the "electric field" and "magnetic field".

Note that the fields are defined everywhere in space and time, regardless of whether or not a charge is present to experience the force. In particular, the fields are defined with respect to what force a test charge would feel, if it were hypothetically placed there.

Note also that as a definition of E and B, the Lorentz force is only a definition in principle because a real particle (as opposed to the hypothetical "test charge" of infinitesimally-small mass and charge) would generate its own finite E and B fields, which would alter the electromagnetic force that it experiences. In addition, if the charge experiences acceleration, for example, if forced into a curved trajectory by some external agency, it emits radiation that causes braking of its motion. See, for example, Bremsstrahlung and synchrotron light. These effects occur through both a direct effect (called the radiation reaction force) and indirectly (by affecting the motion of nearby charges and currents).

Moreover, the electromagnetic force is not in general the same as the net force, due to gravity, electroweak and other forces, and any extra forces would have to be taken into account in a real measurement.

Lorentz force and Faraday's law of induction

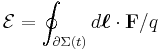

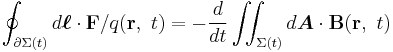

Given a loop of wire in a magnetic field, Faraday's law of induction states:

where:

is the magnetic flux through the loop,

is the magnetic flux through the loop, is the electromotive force (EMF) experienced,

is the electromotive force (EMF) experienced,- t is time

- The sign of the EMF is determined by Lenz's law.

Note that this is valid for not only a stationary wire but also for a moving wire. The Faraday Law (that is valid for a moving wire, for instance in a motor) and the Maxwell Equations the Lorentz Force can be deduced. The reverse is also true, the Lorentz force and the Maxwell Equations can be used to derive the Faraday Law.

Let  be the moving wire, moving together without rotation and with constant velocity

be the moving wire, moving together without rotation and with constant velocity  and

and  be the internal surface of the wire. The EMF around the closed path

be the internal surface of the wire. The EMF around the closed path  is given by:[14]

is given by:[14]

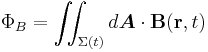

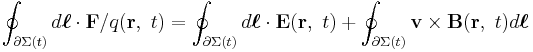

where dℓ is an element of the curve  . The flux ΦB in Faraday's law of induction can be expressed explicitly as:

. The flux ΦB in Faraday's law of induction can be expressed explicitly as:

where

is a surface bounded by the closed contour

is a surface bounded by the closed contour

- E is the electric field,

- dℓ is an infinitesimal vector element of the contour

,

, - v is the velocity of the infinitesimal contour element dℓ,

- B is the magnetic field.

- dA is an infinitesimal vector element of surface

, whose magnitude is the area of an infinitesimal patch of surface, and whose direction is orthogonal to that surface patch.

, whose magnitude is the area of an infinitesimal patch of surface, and whose direction is orthogonal to that surface patch. - Both dℓ and dA have a sign ambiguity; to get the correct sign, the right-hand rule is used, as explained in the article Kelvin-Stokes theorem.

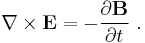

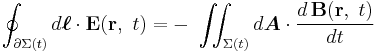

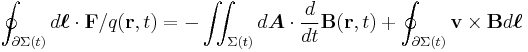

The above result can be compared with the version of Faraday's law of induction that appears in the modern Maxwell's equations, called here the Maxwell-Faraday equation:

The Maxwell-Faraday equation also can be written in an integral form using the Kelvin-Stokes theorem:[15].

So we have, the Maxwell Faraday equation:

and the Faraday Law,

The two are equivalent if the wire is not moving. Using the Leibniz integral rule and that div B = 0, results in,

and using the Maxwell Faraday equation,

since this is valid for any wire position it implies that,

Faraday's law of induction holds whether the loop of wire is rigid and stationary, or in motion or in process of deformation, and it holds whether the magnetic field is constant in time or changing. However, there are cases where Faraday's law is either inadequate or difficult to use, and application of the underlying Lorentz force law is necessary. See inapplicability of Faraday's law.

If the magnetic field is fixed in time and the conducting loop moves through the field, the flux magnetic flux ΦB linking the loop can change in several ways. For example, if the B-field varies with position, and the loop moves to a location with different B-field, ΦB will change. Alternatively, if the loop changes orientation with respect to the B-field, the B•dA differential element will change because of the different angle between B and dA, also changing ΦB. As a third example, if a portion of the circuit is swept through a uniform, time-independent B-field, and another portion of the circuit is held stationary, the flux linking the entire closed circuit can change due to the shift in relative position of the circuit's component parts with time (surface  time-dependent). In all three cases, Faraday's law of induction then predicts the EMF generated by the change in ΦB.

time-dependent). In all three cases, Faraday's law of induction then predicts the EMF generated by the change in ΦB.

Note that the Maxwell Faraday's equation implies that the Electric Field (E) is non conservative when the Magnetic Field (B) varies in time, and is not expressible as the gradient of a scalar field, and not subject to the gradient theorem since its rotational is not zero.

See Landau, L. D., Lifshit︠s︡, E. M., & Pitaevskiĭ, L. P. (1984). Electrodynamics of continuous media; Volume 8 Course of Theoretical Physics (Second ed.). Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann. p. §63 (§49 pp. 205–207 in 1960 edition). ISBN 0750626348. http://worldcat.org/search?q=0750626348&qt=owc_search. M N O Sadiku (2007). Elements of elctromagnetics (Fourth ed.). NY/Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 391. ISBN 0-19-530048-3. http://books.google.com/?id=w2ITHQAACAAJ&dq=isbn:0-19-530048-3.

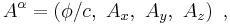

Lorentz force in terms of potentials

If the scalar potential and vector potential replace E and B (see Helmholtz decomposition), the force becomes:

or, equivalently (making use of the fact that v is a constant; see triple product),

where

- A is the magnetic vector potential

is the electrostatic potential

is the electrostatic potential- The symbols

denote gradient, curl, and divergence, respectively.

denote gradient, curl, and divergence, respectively.

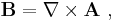

The potentials are related to E and B by

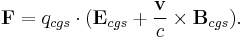

Lorentz force in cgs units

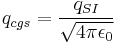

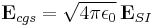

The above-mentioned formulae use SI units which are the most common among experimentalists, technicians, and engineers. In cgs-Gaussian units, which are somewhat more common among theoretical physicists, one has instead

where c is the speed of light. Although this equation looks slightly different, it is completely equivalent, since one has the following relations:

,

,  , and

, and

where ε0 and μ0 are the vacuum permittivity and vacuum permeability, respectively. In practice, unfortunately, the subscripts "cgs" and "SI" are always omitted, and the unit system has to be assessed from context.

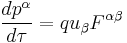

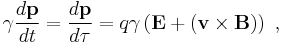

Covariant form of the Lorentz force

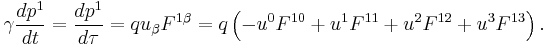

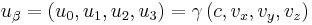

Newton's law of motion can be written in covariant form in terms of the field strength tensor.

-

- where

is c times the proper time of the particle,

is c times the proper time of the particle,- q is the charge,

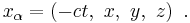

- u is the 4-velocity of the particle, defined as:

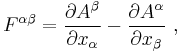

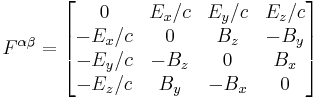

- with γ = Lorentz factor defined above, and F is the field strength tensor (or electromagnetic tensor) and is written in terms of fields as:

-

.

.

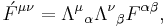

The fields are transformed to a frame moving with constant relative velocity by:

where  is a Lorentz transformation. Alternatively, using the four vector:

is a Lorentz transformation. Alternatively, using the four vector:

related to the electric and magnetic fields by:

the field tensor becomes:[16]

where:

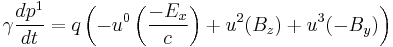

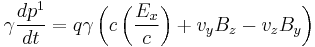

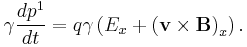

Translation to vector notation

The  component (x-component) of the force is

component (x-component) of the force is

Here,  is the proper time of the particle. Substituting the components of the electromagnetic tensor F yields

is the proper time of the particle. Substituting the components of the electromagnetic tensor F yields

Writing the four-velocity in terms of the ordinary velocity yields

The calculation of the  or

or  is similar yielding

is similar yielding

or, in terms of the vector and scalar potentials A and φ,

which are the relativistic forms of Newton's law of motion when the Lorentz force is the only force present.

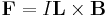

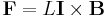

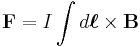

Force on a current-carrying wire

When a wire carrying an electrical current is placed in a magnetic field, each of the moving charges, which comprise the current, experiences the Lorentz force, and together they can create a macroscopic force on the wire (sometimes called the Laplace force). By combining the Lorentz force law above with the definition of electrical current, the following equation results, in the case of a straight, stationary wire:

where

- F = Force, measured in newtons

- I = current in wire, measured in amperes

- B = magnetic field vector, measured in teslas

= vector cross product

= vector cross product- L = a vector, whose magnitude is the length of wire (measured in metres), and whose direction is along the wire, aligned with the direction of conventional current flow.

Alternatively, some authors write

where the vector direction is now associated with the current variable, instead of the length variable. The two forms are equivalent.

If the wire is not straight but curved, the force on it can be computed by applying this formula to each infinitesimal segment of wire dℓ, then adding up all these forces via integration. Formally, the net force on a stationary, rigid wire carrying a current I is

(This is the net force. In addition, there will usually be torque, plus other effects if the wire is not perfectly rigid.)

One application of this is Ampère's force law, which describes how two current-carrying wires can attract or repel each other, since each experiences a Lorentz force from the other's magnetic field. For more information, see the article: Ampère's force law.

EMF

The magnetic force (q v × B) component of the Lorentz force is responsible for motional electromotive force (or motional EMF), the phenomenon underlying many electrical generators. When a conductor is moved through a magnetic field, the magnetic force tries to push electrons through the wire, and this creates the EMF. The term "motional EMF" is applied to this phenomenon, since the EMF is due to the motion of the wire.

In other electrical generators, the magnets move, while the conductors do not. In this case, the EMF is due to the electric force (qE) term in the Lorentz Force equation. The electric field in question is created by the changing magnetic field, resulting in an induced EMF, as described by the Maxwell-Faraday equation (one of the four modern Maxwell's equations).[17]

The two effects are not however symmetric. As one demonstration of this, a charge rotating around the magnetic axis of a stationary, cylindrically-symmetric bar magnet will experience a magnetic force, whereas if the charge is stationary and the magnet is rotating about its axis, there will be no force. This asymmetric effect is called Faraday's paradox.

Both of these EMF's, despite their different origins, can be described by the same equation, namely, the EMF is the rate of change of magnetic flux through the wire. (This is Faraday's law of induction, see above.) Einstein's theory of special relativity was partially motivated by the desire to better understand this link between the two effects.[17] In fact, the electric and magnetic fields are different faces of the same electromagnetic field, and in moving from one inertial frame to another, the solenoidal vector field portion of the E-field can change in whole or in part to a B-field or vice versa.[18]

General references

The numbered references refer in part to the list immediately below.

- Feynman, Richard Phillips; Leighton, Robert B.; Sands, Matthew L. (2006). The Feynman lectures on physics (3 vol.). Pearson / Addison-Wesley. ISBN 0-8053-9047-2: volume 2.

- Griffiths, David J. (1999). Introduction to electrodynamics (3rd ed.). Upper Saddle River, [NJ.]: Prentice-Hall. ISBN 0-13-805326-X

- Jackson, John David (1999). Classical electrodynamics (3rd ed.). New York, [NY.]: Wiley. ISBN 0-471-30932-X

- Serway, Raymond A.; Jewett, John W., Jr. (2004). Physics for scientists and engineers, with modern physics. Belmont, [CA.]: Thomson Brooks/Cole. ISBN 0-534-40846-X

- Srednicki, Mark A. (2007). Quantum field theory. Cambridge, [England] ; New York [NY.]: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-86449-7. http://books.google.com/?id=5OepxIG42B4C&pg=PA315&dq=isbn=9780521864497

Numbered footnotes and references

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 See Jackson page 2. The book lists the four modern Maxwell's equations, and then states, "Also essential for consideration of charged particle motion is the Lorentz force equation, F = q ( E+ v × B ), which gives the force acting on a point charge q in the presence of electromagnetic fields."

- ↑ These definitions use Helmholtz's theorem. Because divB = 0 (Gauss's law for magnetism), Helmholtz's theorem proves that we can define a vector field A (called the magnetic potential) such that B = ∇ × A. From the Maxwell-Faraday equation, ∇ × E = −∂t B so ∇ × [ E + ∂t A ] = 0. Applying Helmholtz's theorem again to E + ∂t A, which has zero curl, we find that we can define a scalar field ɸ (called the electric potential) with E + ∂t A = −∇ɸ. The equation for B automatically satisfies ∇•B = 0, that is, demonstrates that B is a solenoidal vector field. Also, the equation for E shows that it can have two different components: a conservative or irrotational vector field component (which originates in electric charges) and a nonconservative or curl component (which originates in the Maxwell-Faraday equation). For more details, see magnetic potential and electric potential.

- ↑ See Griffiths page 204.

- ↑ For example, see the website of the "Lorentz Institute": [1], or Griffiths.

- ↑ Meyer, Herbert W. (1972). A History of Electricity and Magnetism. Norwalk, CT: Burndy Library. pp. 30–31.

- ↑ Verschuur, Gerrit L. (1993). Hidden Attraction : The History And Mystery Of Magnetism. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 78–79. ISBN 0195064887.

- ↑ Darrigol, Olivier (2000). Electrodynamics from Ampère to Einstein. Oxford, [England]: Oxford University Press. pp. 9, 25. ISBN 0-198-50593-0

- ↑ Verschuur, Gerrit L. (1993). Hidden Attraction : The History And Mystery Of Magnetism. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 76. ISBN 0195064887.

- ↑ Darrigol, Olivier (2000). Electrodynamics from Ampère to Einstein. Oxford, [England]: Oxford University Press. pp. 200, 429–430. ISBN 0-198-50593-0

- ↑ Darrigol, Olivier (2000). Electrodynamics from Ampère to Einstein. Oxford, [England]: Oxford University Press. p. 327. ISBN 0-198-50593-0

- ↑ See Griffiths page 326, which states that Maxwell's equations, "together with the [Lorentz] force law...summarize the entire theoretical content of classical electrodynamics".

- ↑ That is, a first-principles approach might be approximated to make calculation possible without complications that are not very significant to the results. For example, a metallic boundary might be approximated as having infinite conductivity. A statistical mechanical model of a plasma might approximate the treatment of collisions with boundaries and between particles.

- ↑ See, for example, Jackson p777-8.

- ↑ Landau, L. D., Lifshit︠s︡, E. M., & Pitaevskiĭ, L. P. (1984). Electrodynamics of continuous media; Volume 8 Course of Theoretical Physics (Second ed.). Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann. p. §63 (§49 pp. 205–207 in 1960 edition). ISBN 0750626348. http://worldcat.org/search?q=0750626348&qt=owc_search.

- ↑ Roger F Harrington (2003). Introduction to electromagnetic engineering. Mineola, NY: Dover Publications. p. 56. ISBN 0486432416. http://books.google.com/?id=ZlC2EV8zvX8C&pg=PA57&dq=%22faraday%27s+law+of+induction%22.

- ↑ DJ Griffiths (1999). Introduction to electrodynamics. Saddle River NJ: Pearson/Addison-Wesley. p. 541. ISBN 0-13-805326-X.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 See Griffiths pages 301–3.

- ↑ Tai L. Chow (2006). Electromagnetic theory. Sudbury MA: Jones and Bartlett. p. 395. ISBN 0-7637-3827-1. http://books.google.com/?id=dpnpMhw1zo8C&pg=PA153&dq=isbn=0763738271.

Applications

The Lorentz force occurs in many devices, including:

- Cyclotrons and other circular path particle accelerators

- Mass spectrometers

- Velocity Filters

- Magnetrons

In its manifestation as the Laplace force on an electric current in a conductor, this force occurs in many devices including:

|

|

See also

|

|

|

External links

- Interactive Java tutorial on the Lorentz force National High Magnetic Field Laboratory

- Lorentz force (demonstration)

- Faraday's law: Tankersley and Mosca

- Notes from Physics and Astronomy HyperPhysics at Georgia State University; see also home page

![\mathbf{F}=q[\mathbf{E}+(\mathbf{v}\times\mathbf{B})].](/2010-wikipedia_en_wp1-0.8_orig_2010-12/I/97df3474bc68a2c0cf632c3653a6d8bd.png)